Bài viết nguy hiểm, luận điệu bênh TQ. Cần đọc để hiểu và xây dựng lập luận phản bác.

------

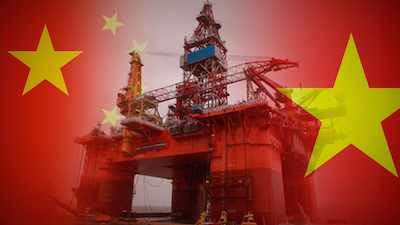

China-Vietnam Dispute in the South China Sea

Vietnam asserts that the Chinese rig lies on Vietnam’s continental shelf. Under the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Seas (Convention), to which both Vietnam and China belong, if the only continental shelf that is relevant is the one emanating from Vietnam’s coast line, Vietnam would be able to assert a 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone, which gives it exclusive rights to all mineral and hydrocarbon resources within that zone.

However, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has insisted that China’s rig was placed “completely within the waters of China’s Paracel Islands” and lies within a separate and more proximate continental shelf that those islands would generate under the terms of the Convention. Based on this premise, China would be able to assert its own 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone within which its rig lies, assuming that it does indeed have lawful sovereignty over the islands themselves.

Thus, there are competing claims of “exclusive economic zone” as defined under the Convention. There are also competing claims over which country has legal sovereignty to the Paracel Islands, as to which the Convention provides no direct guidance. Indeed, China claims that it is Vietnam which is violating international law, whose basic principles supporting China’s rights to the islands and related maritime space are broader than the provisions of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea alone.

Vietnam’s UN mission sent Secretary General Ban Ki-moon a letter enclosing a diplomatic note from the Vietnamese Foreign Ministry dated May 4, 2014, outlining the basis for its claims and accusing China of refusing to end violations of Vietnam’s alleged sovereignty and jurisdiction over what it claims as its exclusive economic zone. The Vietnamese mission’s letter to Ban Ki-moon asked him to circulate it as an official document of the 68th session of the General Assembly.

China rejects Vietnam’s accusations as “slander” intended to mislead the international community about the actual situation in the South China Sea.

“On the one hand, they have been increasing their damaging and harassing activities on the scene, while internationally everyone has seen they have been unbridled in starting rumours and spreading slander, unreasonably criticising China,” its foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said at a press briefing on June 10th. She added that China had to explain the “real situation” to be clear “about Vietnam’s real aim in wantonly hyping things up.”

To back up its side of the dispute, China’s deputy ambassador Wang Min sent China’s position paper to Ban Ki-moon on June 9th and, just as Vietnam had done, asked him to circulate it to all UN General Assembly member states. China’s position paper accused Vietnam of infringing on its sovereignty and “illegally and forcefully disrupting the normal operation of the Chinese company on the sea.” China said in its position paper that it has exercised “great restraint” while taking “necessary preventive measures.” These measures consisted of the dispatching of Chinese ships to the site “for the purpose of ensuring the safety of the operation, which effectively safeguarded the order of production and operation on the sea and the safety of navigation.” China claimed that it has reached out to Vietnam on multiple occasions to request that it “stop its illegal disruption,” but that such disruption is still continuing.

Both countries have professed that they want to find a peaceful solution, but a top Vietnam official warned that “all restraint had a limit.” The “limit” on Vietnam’s “restraint” has evidently already been reached. Vietnam has taken a series of provocative actions, according to China’s position paper, which provided several examples. Shortly after the Chinese drilling operation started, Vietnam has sent dozens of vessels, some armed, to the site in an attempt to disrupt the operation. Vietnamese ships have rammed Chinese ships guarding the drilling rig, China’s position paper said. “Vietnam also sent frogmen and other underwater agents to the area, and dropped large numbers of obstacles, including fishing nets and floating objects, in the waters,” the paper added.

The Vietnamese government’s provocative actions have set off anti-China demonstrations in Vietnam, which has led to violence against Chinese nationals and property. Four Chinese nationals were killed and 300 others injured, according to China’s position paper.

The Vietnamese government has not denied outright that such events took place, but essentially has laid the blame completely on China. It has accused China of ramming its boats and claimed that a Chinese vessel plowed into one of its fishing boats before it sank on May 26th. The Chinese said they were on the defensive while Vietnamese vessels were attacking Chinese fishing boats.

China said that it is only continuing explorations that have gone on in related waters for the past 10 years. China’s position paper set forth the historical basis for its claim that the “Xisha Islands are an inherent part of China’s territory.” It traced the establishment of Chinese jurisdiction over the islands back to the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1126 AD). China added that Vietnam’s current posture of confrontation is at odds with the prior acknowledgment or acquiescence by successive Vietnam governments of China’s sovereignty over these islands.

Vietnam has offered its own historical and legal narrative to back its claims. It has also denied that prior Vietnamese governments had acknowledged China’s sovereignty over the Paracel Islands, which it said China had acquired by force in 1974. Forty years of China’s control over the Paracel Islands, which were incorporated into Hainan province by Beijing, does not provide China with rights under international law to assert sovereignty over the islands, according to Vietnam.

Vietnam’s historical connection to the Paracel Islands does not appear to go as far back as China’s. There are some Chinese cultural relics in the Paracel islands dating from the Tang and Song eras, going as far back as the seventh century A.D., and there is some evidence of Chinese habitation on the islands during these periods. It was not until the 1460–1497 period under the reign of Emperor Le Thanh Tong that the Vietnamese began conducting commercial activities in the area.

During the twentieth century, while China asserted its own direct sovereignty over the islands, Vietnam’s claims are essentially derived from the actions of a European colonial power. In 1930, France claimed the islands on behalf of its protectorate as part of French Indochina. In 1932, French Indochina and the Nguyen dynasty of Vietnam annexed the islands. On July 27, 1932, the Chinese Foreign Ministry instructed the Chinese Envoy to France to lodge a diplomatic protest to the French Foreign Ministry and to deny France’s claims to the Paracel Islands, which China claimed as its own. Despite repeated Chinese protests, French troops invaded and occupied the Paracel Islands on July 3, 1938. Japan took the islands during World War II, but they were handed over to Republic of China control from Japan after the 1945 surrender of Japan.

After the fall of the nationalist regime in China in 1949, the successor Chinese government gained control of the eastern half of the Paracel Islands. The remainder were held by Franco-Vietnamese forces. In 1956, after the French’s withdrawal from Vietnam, South Vietnam replaced the French in terms of claiming control of the islands. However, North Vietnam sided with China at the time, recognizing China’s claim that the breadth of its territorial sea was twelve nautical miles, which applied to all its territory, including the Paracel Islands. On January 19, 1974, the Battle of the Paracel Islands occurred between China and South Vietnam. After the battle, China gained control over the entire Paracel Islands.

Only after North Vietnam won its own war against South Vietnam and unified the country in 1975 did the Socialist Republic of Vietnam revive the claims of South Vietnam to the Paracel Islands that North Vietnam, which defeated South Vietnam, had rejected in favor of China’s claims.

Vietnam’s claim, that the Paracel Islands and surrounding waters where China’s rig is located are within its exclusive economic zone under international law, rests largely on its interpretation of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Its argument is two-fold. First, it relies on the premise that the only continental shelf that is relevant in establishing the baseline for defining its claim to an exclusive economic zone is the one emanating from Vietnam’s own coast line. However, it can be argued that the Paracel Islands themselves generate a separate and more proximate continental shelf in view of the history of habitability on those islands, including by Chinese fisherman who inhabited the Paracel Islands for much of the year during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Under Article 121(2) of the Convention, an island can have its own territorial sea, contiguous zone, exclusive economic zone and continental shelf.

Secondly, Vietnam argues, even if the Paracel Islands themselves could be deemed as the baseline for making claims to a separate continental shelf and resulting exclusive economic zone, Vietnam has sovereignty to the Paracel Islands, not China. According to this line of argument, Vietnam would therefore have the undisputed right to declare an exclusive economic zone encompassing the Paracel Islands and surrounding waters even though it has no actual control over the territory at issue.

However, the Convention does not bestow that right on Vietnam. In fact, Article 298 of the Convention provides that “any dispute that necessarily involves the concurrent consideration of any unsettled dispute concerning sovereignty or other rights over continental or insular land territory shall be excluded from” any submission of a dispute for conciliation under the auspices of the Convention.

Vietnam claims that China’s taking of the western portion of the Paracel Islands by force in 1974 and assertion of sovereignty over all of the islands are in violation of international law. However, Vietnam’s own claims are derivative from the assertion of control of the islands by means of force that the colonial power France exercised during the 1930’s, in contravention of China’s pre-existing sovereignty claims and over subsequent repeated protests by China. Moreover, China argues, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam is itself was stopped under international law from claiming sovereignty to the Paracel Islands now, given that it is the successor state to the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) that had issued official statements in support of China’s claim to the Paracel Islands on several occasions during the 1950’s and 1960’s. China’s estoppel argument is a compelling one.

Rather than risk further escalation of tensions and confrontation that could spin out of control, Vietnam should accept China’s offer of direct communication at appropriate levels to resolve the dispute peacefully. Since both sides have contacted Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, perhaps he can use his good offices in trying to help China and Vietnam reach an amicable solution that is mutually beneficial. At the same time, the Obama administration would do well to butt out unless both parties ask for its assistance.

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét